(The short story “Minimum Payment Due” by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh appeared in the November 25th, 2024 issue of The New Yorker.)

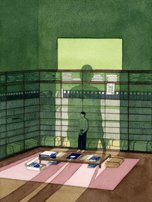

Illustration by Hannah K. Lee

If there is one issue that no one talks about, but is shaping the future of America in profound ways; it is debt. Student loans, medical bills, car loans, mortgages, and especially, credit cards. Having debt was unthinkable to my grandparents, as that was a sign of a type of moral failure, as you lacked the ability to live within your means. Now, everyone has some form of debt, and the way it’s going, our collective debt is only going to get bigger. “Minimum Payment Due” by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh deals with debt, and the shame and frustration that comes with it. The story also explores the desire for solutions, and faith that resolutions are out there.

Overly Simple Synopsys: A guy has way too much credit card debt, and can’t get out from under it. He looks for relief in self-help books, therapy, and in the end, an old friend from high school invites him to a “graduation” with an unexpected outcome.

What really worked for me was the protagonist, and how he found himself in his debt, and how he looked for ways out of it. Oh, the narrator is completely unreliable, as he cannot seem to stop lying to everyone else, including himself, so I see no reason why he would tell us the truth. And I think that plays to the shame that comes with debt. There is also an element that this debt is a form of addiction for the narrator, as he just cannot stop spending money, looking for a purchase that will make him feel better, but only leads him to spend more money. And that’s what I liked most about this story, how it very subtly parallel debt and addiction. I felt that Saïd Sayrafiezadeh was making a very good point that capitalism and consumerism lead to debt addictions in some people, leaving them feeling vacant, thus looking for someone or something to deliver them from their crisis.

Unfortunately, I had issues with the ending of the piece. It was the whole final section where the narrator goes to his friends “graduation.” I wasn’t sure what point was trying to be made. That debt is just a cycle that repeats over and over again. Or that people in debt have to admit that they are powerless against it, like in AA. Or was the narrator just a cynical person who never had the intention of solving his issues. I feel the point was to be ambiguous, letting the reader decide, but it left me feeling frustrated. Did the narrator learn anything? Does the narrator want to learn anything? Either thought left the story feeling incomplete.

All in all, I have to say that I did enjoy the piece, with one clear exception. I have said this several times of late when it comes to New Yorker stories, but this one felt like it was the first chapter of a book, or at least a much larger story. I hope that’s what it is, because I would be curious to read that book.